“We don’t do grief. Yet grief still does us.” (About Grief, Marasco & Shuff, 2010)

As in my previous post on eulogies, this reflection was inspired by a book currently on my desk. I’m taking a break from my day-to-day work and for 4 weeks, living in a different city with —to my delight — a more extensive library system.

About Grief begins with a somewhat comical story of how authors Marasco and Shuff were misunderstood to be writing a book about Greece, not grief. And then, when the authors clarified, some were puzzled why two men, both journalists, who did not seem to have dark clouds above their heads would spend time and energy researching and writing about grief. I can just imagine someone shaking her head saying, “Of all things…grief? Grief? Who would want to talk and read and write about THAT?”

They continue, “After this initial reaction, though, people would lean forward, intrigued, wanting to know more. Once they saw the coast was clear to actually talk about this taboo subject, a flood of thoughts, feelings, questions, and above all, personal stories poured out of them.” (About Grief. Introduction.)

Bill and I have had similar responses — me less so, because a focus on grief makes more sense with Counsellor as your job title. But for an Investment Advisor? What investment advisor wants to embark on a project focused on grief?

So, to start with we both wrote personal Why statements when we launched this site. If you haven’t read them, they are here: Ruth “Why Suddenly Single” and Bill “Why Suddenly Single“.

But perhaps a broader response to “Why?” needs to be explored and then explored again.

“We don’t do grief. Yet grief still does us.”

As I neared the end of my masters program, a professor suggested we start thinking about what area of counselling we wanted to specialize in. I already knew Grief and Loss would be one of mine. I had recently read that this current group of young adults (some of whom were my classmates) were the first in human history where a significant number of them had reached adulthood without experiencing the death of someone close to them. After all, infant mortality was down, vaccinations had wiped out numerous killer diseases, and other formerly common causes of death had decreased significantly.

I shared this tidbit with those at my table and a number of my classmates agreed. One young woman in her late 20s said that she absolutely could not focus on grief and loss because she had never experienced a death. All four of her grandparents were alive and healthy and she had never lost a friend or extended family member. The closest she’d come was vicarious grief as her former home community mourned the deaths of a number of young men killed by a mountain avalanche triggered by snowmobiling. She did not know any of them personally but the community was small enough that she knew people who did. Mere months later, one of those classmates experienced the sudden death of her grandfather. Eight years later, I’m sure I can safely say that others around that table have done the same.

As an older student, I was already different from my classmates. And, most certainly I was different in my experiences with grief and loss. In fact, my earliest childhood memory is the death of my young uncle.

“We don’t do grief. Yet grief still does us.”

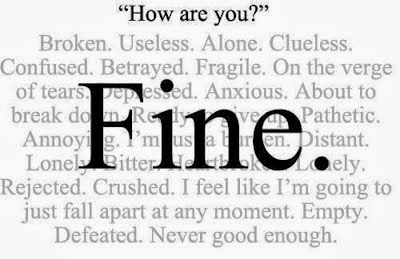

Our western culture wants to side-step grief. We push people to be fit for work and life quickly — far too quickly — after a death. We are uncomfortable with grief’s intensity and look away. We don’t know what to say when our friends are grieving. We scrap with our families when death happens, rather than reach out and offer a genuine and heartfelt presence. We miss many instances of what grief expert Kenneth Doka calls Disenfranchised Grief — the grief that happens when the loss or the relationship isn’t acknowledged. (For more on disenfranchised grief, see Wikipedia: Disenfranchised grief)

Yet… grief still DOES us. It does us in. It stops us in our tracks. It changes our lives, altering the paths we thought we were on — forever. If you are reading this having lost a spouse — which is the focus of Suddenly Single Survival Guide — you know grief intimately.

As I’ve paged through About Grief, I’ve thought of my clients, specific people to whom I will recommend this book.

I imagine them resonating with these words, snippets from the pages of About Grief.

Grief is what happens after all the drama ends.

Grief teaches you a lot about yourself.

Grief will tell you when it’s the real thing.

And, particularly with the quote from poet Donald Hall, who after losing his wife at age 46 wrote this small poem:

Distressed Haiku

You think that their

dying is the worst

thing that could happen.

Then they stay dead.

“We don’t do grief. Yet grief still does us.”